SCLC Patients with LEMS Have Better Long-term Survival, Study Suggests

shutterstock/Von solar22

Patients who have Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) associated with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) seem to have better long-term survival than cancer patients without this neurologic syndrome, a study shows.

The study, “Long-term survival in paraneoplastic Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome,” was published in the journal Neurology.

LEMS is an autoimmune disorder caused by abnormal interaction between nerve cells and muscles. Overproduction and accumulation of antibodies will block the electrical signals of nerve cells, preventing muscles from receiving them and reacting accordingly.

About 50-60% of LEMS patients have cancer, most of which is SCLC.

Previous studies have suggested an association between incidence of LEMS and long-term survival of cancer patients. However, this relationship remains poorly understood.

Researchers retrospectively reviewed the clinical records of 313 patients with SCLC from the Nottingham Trent region of the United Kingdom.

Among these SCLC patients, 13 (4.2%) had LEMS, 279 (89.1%) had no evidence of a cancer-associated neurological disease at diagnosis and during follow-up, and 21 patients (6.7%) had SCLC plus a neurological disorder other than LEMS.

Moreover, the researchers added 18 patients with LEMS-SCLC to their sample, recruited via the British Neurological Surveillance Unit up to November 2014.

Almost all patients with LEMS-SCLC (29 of 31) were first diagnosed with LEMS within the year before the cancer was detected. Only 10 patients with LEMS had symptoms suggestive of an underlying chest malignancy, such as cough, chest pain, and breathlessness, by the time of LEMS diagnosis.

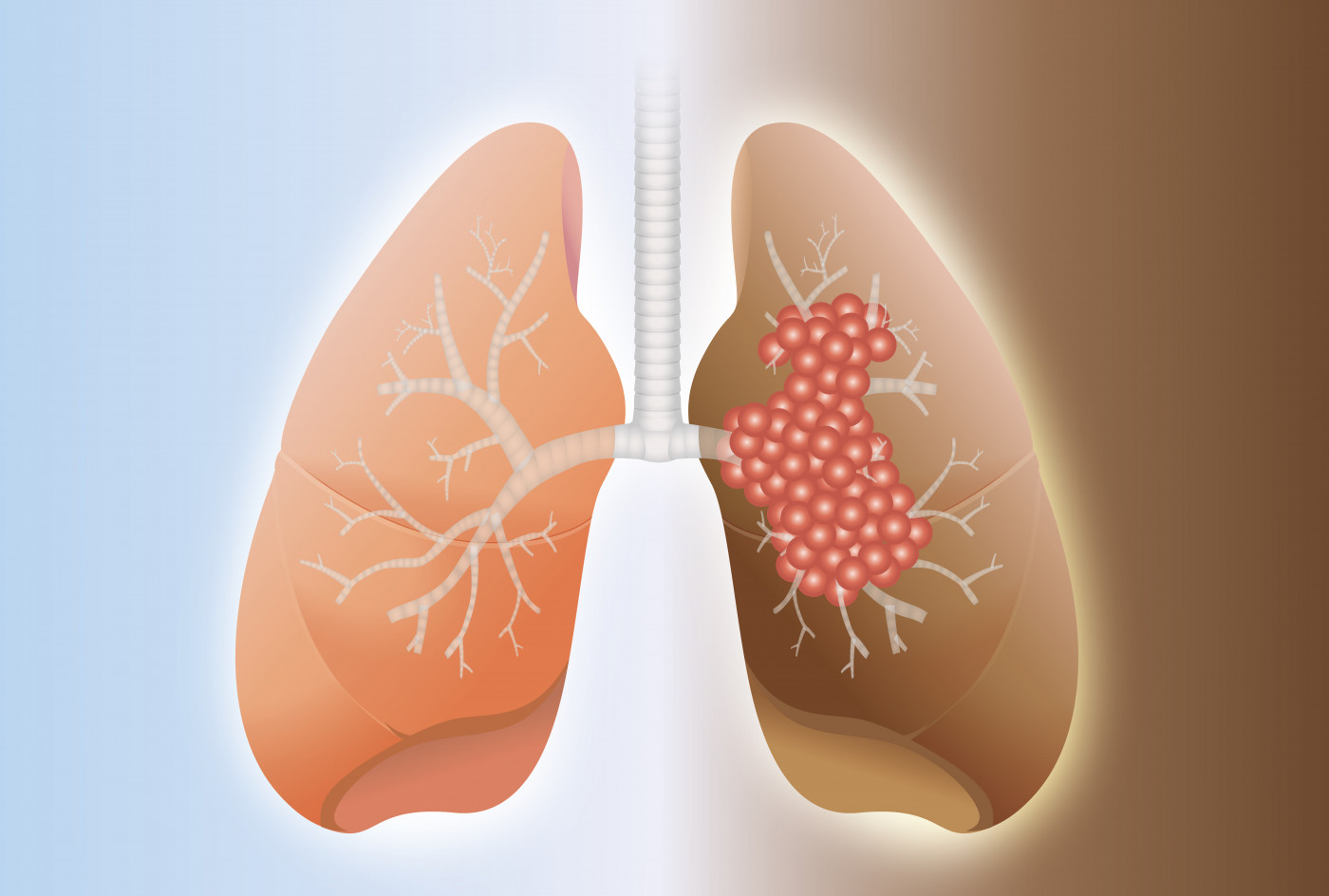

LEMS patients had more frequently limited SCLC tumors — affecting just one lung — compared to patients with SCLC alone (61% versus 34%).

Treatment regimens used were similar among all patients, regardless of the presence of neurological disorders, and were based on chemotherapy and surgical tumor resection.

Evaluation of patients’ survival revealed that that those with LEMS-SCLC lived approximately double the time from cancer diagnosis than patients without neurological disease (18 vs 9.5 months).

It is thought that blood-circulating proteins from patients with LEMS-SCLC are capable of reducing the ability of cancer cells to proliferate and grow. However, although LEMS patients had greater levels of circulating VGCC antibody, the team found that these could not explain the reported difference in survival time between the two groups.

Further analysis considering other SCLC survival prognostic factors, including disease extent, age, gender, and sodium values, showed that the presence of LEMS with SCLC conferred a significant survival advantage independently of the other prognostic variables.

Indeed, LEMS-SCLC patients had a 43% reduced risk of death compared to other SCLC patients.

“Improved SCLC tumor survival seen in patients with LEMS and SCLC may not be due solely to lead time bias,” researchers said. Also, they said, “the same degree of survival advantage is not seen in patients” with other cancer-related neurological syndromes other than LEMS presenting before SCLC diagnosis.”