Low-Frequency RNS May Help Distinguish LEMS From MG: Study

Repetitive stimulations were given to 17 LEMS, 44 MG patients during the study

Written by |

Muscle responses to low-frequency repetitive nerve stimulation in people with Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) were different from those of patients with myasthenia gravis (MG), a study reported.

Because LEMS and MG are both autoimmune diseases marked by muscle weakness and other overlapping symptoms, this test may help distinguish the two conditions, the researchers noted.

The study’s abstract, “Low-Frequency repetitive nerve stimulation studies in myasthenia gravis and Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome patients,” was presented at the 32nd International Congress of Clinical Neurophysiology (ICCN) of the IFCN on Sept. 4–8 in Geneva, Switzerland.

LEMS is caused by a mistaken immune response that targets certain molecules on nerve cells in the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) — a specialized synapse, or gap, where nerve cells communicate with the muscles they control. MG is a similar condition caused by a misdirected immune attack on components in the muscle side of the NMJ.

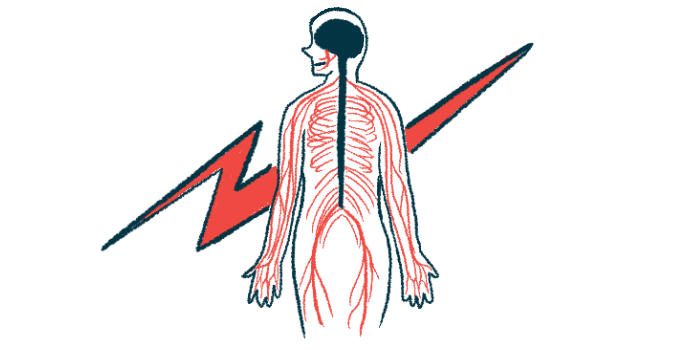

Repetitive nerve stimulation (RNS) is an assessment tool used for NMJ-related diseases whereby a motor nerve is repeatedly stimulated by electrical signals.

In healthy muscle, the muscle-based electrical responses after RNS remain above the threshold needed to trigger a muscle contraction. With NMJ defects, the response drops below this threshold and, with each stimulation and more muscle fibers failing to contract, the response strength gradually diminishes.

The aim of this study by investigators at Peking Union Medical College Hospital, China was to see if RNS using low frequency electrical signals could distinguish between LEMS and MG.

The study involved 17 LEMS patients (14 males and three females) and 44 MG patients (17 males and 27 females). Repetitive stimulations were applied to the muscles of the hand, upper back/neck, and eyelids at a frequency of 3 Hz for at least two trains of signals, with each train comprising 10 stimuli.

In all LEMS patients, initial muscle electrical wave responses were weak. Of the 31 analyzed muscles, 25 (80.6%) showed a weaker response. In 24% of these muscles, the lowest response strength was seen after the seventh stimuli. Lowest response strengths were recorded in 32% of the muscles after the eighth stimuli and in 20% after the ninth stimuli.

Linear correlations representing a steady decline in responses were found within the first five wave responses.

In comparison, 67 muscles from MG patients also showed weaker responses, with the lowest strength response waves across affected muscles seen in 34.3% of the cases after the fourth stimuli and in 53.7% of the cases after the fifth. Within the 10 wave responses, linear correlations were found from waves 1–3.

On average, the weakest response wave occurred after the second stimulus in both groups. In the third wave, muscle responses dropped by 59.5% in LEMS patients, while they fell by 86.6% in those with MG. In LEMS patients, muscle responses were 87.9% lower in the fifth wave, and 16% of their muscles showed weak responses after stimuli four or five.

“In the [low frequency] RNS examination of MG patients, 88% showed the lowest amplitude at wave 4 or 5, and the 3rd wave could reach 80% of the maximum decrement,” the researchers wrote. “In patients with LEMS, the lowest amplitude was more likely to be seen in the 7th, 8th, and 9th wave.”

“Therefore, in such patients, [low frequency] RNS may be helpful to [differentiate] MG and LEMS,” they wrote.